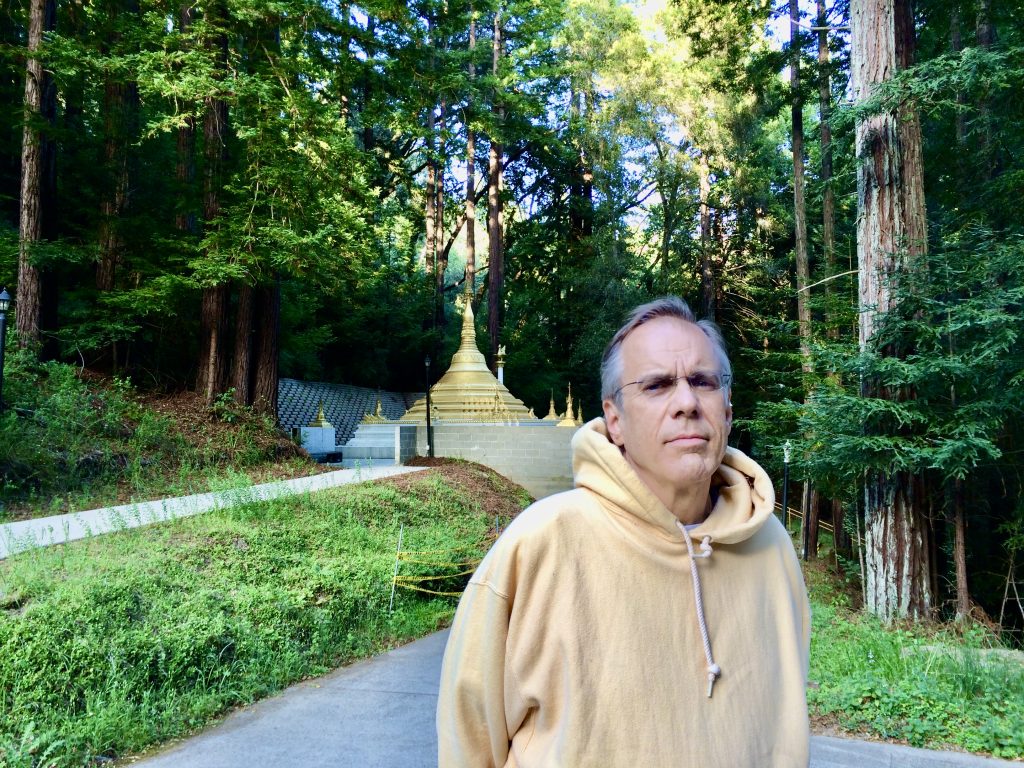

The following is a review of Evan Thompson’s book “Why I Am Not a Buddhist” by Don Asper, a long-time disciple of H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III. Don is a gifted musician and retired IT person who often brings his background in philosophy and the evolving world of cognitive science and related matters to bear on our discussions of Buddhism. I agree with his findings and hope you find them useful. We welcome your comments. Zhaxi Zhuoma

“April 19, 2021: Why I Am Not a Buddhist” is a highly readable, in-depth critique of some important aspects of Buddhist thinking – past and present. Its author, Evan Thompson, is a philosopher specializing in the developing interplay between Buddhism, cognitive science and the philosophy of mind. He has worked with the Dalai Lama and the Mind and Life Institute. Much of “Why I Am Not a Buddhist” is a synthesis of major research Thompson had previously done, such as for the book “The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience”. The concept of “embodied cognition”, first proposed in “The Embodied Mind” figures prominently in Chapter 4 of “Why I Am Not a Buddhist”.

Thompson’s purpose is not to impugn Buddhism’s value in the modern world. In fact, he says [p. 58]: “[The] view that Buddhism is fundamentally important, especially for our world today, is one that I share”. He provides many interesting and cogent insights by viewing Buddhism from different angles, “from the outside”, thereby bringing Buddhism into sharper focus. His ideas do not defeat or diminish Buddhism, but instead make apparent the seriousness of the scrutiny that Buddhism has undergone both recently and in the course of its long history, and its ability to remain relevant.

Thompson’s reasons for not being a Buddhist are not simple or dogmatic. Rather than simply stating his reasons, he reconstructs the arguments that led to them. One can thereby appreciate their complexity – a complexity that is further compounded by their inter-relatedness. Thompson discusses a variety of diverse topics — one per each of the book’s six chapters. Each of these chapters gives the reader an understanding of the size of the problem it discusses, as well as the likelihood of clearing that problem up. Together the chapters demonstrate the complexity and inter-relatedness of their Buddhist subject matter. Together they also demonstrate to the reader that several underlying issues are related to more than one of the chapter topics. These make the book’s seemingly disparate chapter topics into a network of relationships and relate the aspects of Buddhism Thompson has chosen to one another.

This review cannot do justice to the pattern of those relationships; it can only note a few that Thompson has pointed out. Instead, our purpose in writing this review is to find aspects of modern Buddhism where H. H. Dorje Chang Buddha III’s teachings are especially relevant. Fundamental issues like those mentioned above better suit this purpose than the narrower, more academic inadequacies that Thompson sets out to describe. Those underlying issues have greater impact on peoples’ understanding and practice of Buddhism than the more specialized topics the book’s chapters are meant to cover, and as such have a greater relevance to Buddhist practitioners overall. They are also closer to the cause of the problems Thompson’s chapters describe, than to the symptoms. What issues gleaned from “Why I Am Not a Buddhist” will we address? They are:

- Stances and schools

- Terms and word usage

- Buddhism and science

- Modernizing Buddhism

- Mind is not brain

Stances and schools

Ever since early in Buddhist history there have been Buddhist schools. Each of these schools typically emphasizes and elaborates specific parts of what Shakyamuni Buddha taught. There have also been numerous commentators of Buddhist texts with differing opinions about Shakyamuni Buddha’s teachings. The debates concerning some Buddhist concepts have fostered greater understanding and consequent growth of Buddhist philosophy, but, they have also created uncertainty in many areas of Buddhist thought. This can make Buddhism seem vague and perhaps more mystical than it actually is. This uncertainty extends back to the words of Shakyamuni Buddha, preserved in the Pali Canon. H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III has told us that although what Shakyamuni Buddha actually taught was without error, misinterpretations and incorrect understanding of the Buddha’s teachings began immediately after He left this world. Over 2,500 years of being translated into different languages and cultures as Buddhism migrated around the world has only compounded the problem. H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha came to this world at this time to address these problems.

Here is an example of such a problem: In chapter 2, “Is Buddhism True?”, Thompson is in pursuit of what it means to be unconditioned, [p. 80]: “Traditionally, the unconditioned is that which is free from all causation, from all compounding (putting together and building up) of unawakened existence.” He then refers to the notion of nirvana being unconditioned, but notes [p. 80]: “It’s important to emphasize that Buddhism contains different ways of thinking about nirvana, the unconditioned.” This idea leads Thompson to say [p. 81]: “…naturalistic Buddhists think that once we drop the rebirth cosmology, all we have left is the unconditioned as a psychological state.” At this point, we are torn between accepting the proliferation of these concepts or disqualifying naturalistic Buddhists as heretics.

In classical Buddhist parlance, such proliferation of concepts (papanca) is considered unwholesome and should be restrained. It is a characteristic of conceptual thinking that creates divisiveness and makes Buddhism harder to convey. In this case, it also puts a strain on Buddhist inclusiveness.

As can be seen from the example above, papanca can develop beyond individual concepts into groups of concepts or trends, such as “naturalistic Buddhism”, which Thompson speaks of in various parts of the book. It can then develop into schools of thought. In a way, this is appropriate and what we should expect. Religions and philosophies develop gradually as a result of such thinking. On the other hand, such conceptual proliferation can lead to the possible loss of Shakyamuni’s original teachings through confusion, forgetfulness and misunderstanding. Thompson himself expresses dismay concerning this state of affairs. He says [p. 155]: “…[W]e might wonder whether these Buddhist traditions all converge on one and the same essential realization, given their significant differences in doctrine, philosophy, and meditation practice. Simply asserting such convergence runs the risk of smuggling in one particular viewpoint in the name of being universal.” To him, the disparities between Buddhist traditions do not appear remediable, but he hopes nonetheless that there is a single message within the network of proliferations.

Besides “traditional Buddhism”, “Why I Am Not a Buddhist” mentions or discusses the following proliferating trends in Buddhist studies:

- neural Buddhism

- Buddhist exceptionalism

- Buddhist modernism

- cosmopolitan Buddhism

- naturalistic Buddhism

Prescription

The teachings of H. H. Dorje Chang Buddha III should be propagated to perpetuate the original true meaning of the Dharma. This includes his teachings on cultivation, the development of bodhichitta or ultimate compassion, and the nature of reality as expressed in the Prajnaparamita Sutra.

By doing so, the proliferation of misinformation about what the Buddha taught can be reduced and the number of good practitioners will increase. It is unfortunate that many of these teachings are not yet available to those who cannot read or understand Chinese.

Terms and word usage

Uncertainty about the meanings of words is a major cause of the proliferation of misinformation relating to Buddhism. Thompson discusses several important Buddhist terms whose meanings are uncertain, including: “self”, “awakening”, “liberation” and “concept”. Chapter 5, “The Rhetoric of Enlightenment”, is devoted entirely to the difficulties of understanding what “enlightenment” means. Many problems arise because Buddhism, which is ostensibly empirical and hence scientific, relies heavily on private experience to justify its assertions – especially meditative experience. But, private experience is not easily communicated or corroborated. So, Buddhist terms that refer to it cannot be clearly defined.

Thompson depicts how this reliance on private experience ultimately requires that we both know about and understand Shakyamuni Buddha’s enlightenment experience. Without that knowledge it is impossible to categorically prove whether some fundamental ideas about Buddhism are true or false. For example, Thompson describes the quandary of a movement he calls the “Buddhist modernists” [p. 155]: “They [i.e. the Buddhist modernists] think they can minimize faith or dispense with it altogether, while still being able to say what ‘enlightenment’ means. One way they try to do this is by appealing to the enlightenment experience of the ‘historical Buddha’. But this is a nonstarter, for the reasons we’ve already seen. We have no access to the Buddha as an actual person rather than a mythic hero, and the earliest accounts of the content of his awakening are equivocal.”

Without authoritative knowledge about Shakyamuni’s enlightenment experience we must rely on our faith in the framework of ideas He developed when asking questions about Buddhism. The following comments Thompson made about “nirvana” could thus be applied to many problematic Buddhist terms [p. 156]: “If you accept the religious framework of Buddhism, which is fundamentally premised on faith in nirvana, you can give answers to these questions. If you’re outside the framework of that faith, it’s not clear you can say anything meaningful.”

It is not surprising that after 2,500 years there is some uncertainty about what Shakyamuni Buddha thought and said. To rectify this, it appears that we need to find an accepted authority who can answer these questions in Shakyamuni Buddha’s absence. Part of the difficulty of finding someone with the authority to speak for Shakyamuni Buddha is that the person’s authority must apply to Shakyamuni Buddha’s private experience, including His enlightenment. But, even if Shakyamuni Buddha Himself were available to answer our questions, we still might be at a loss to understand what He is telling us, and to translate His words into other languages. Furthermore, people would still need to listen to what Shakyamuni Buddha has to say, to take it seriously and accept it. Clearly, the Buddha’s message cannot be communicated perfectly to everyone using language. What then is the optimal way to convey the Buddha’s words, so the greatest number of people will understand them and will consequently be able to attain liberation and enlightenment?

Prescription

Many people believe that H. H. Dorje Chang Buddha III has the wisdom needed to clarify fundamental issues concerning Buddhist principles and practice. His discourses and especially publications such as “Learning from Buddha”, “What Is Cultivation?”, “Imparting the Absolute Truth Through the Heart Sutra” and “The Supreme and Unsurpassable Mahamudra of Liberation” are all teachings that do clarify much of what we know as Buddhism today. We only need to have them available in English and accessible to Western practitioners and scholars.

Buddhism and science

One of the biggest advantages that people have seen in Buddhism is that its doctrines are compatible with science. There are strong and weak claims in this regard. The strong claim is that Buddhism is a “science of mind” which can co-exist with the sciences but goes beyond them. For example, Thompson says the following of Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche [p. 38]: “He allows that Buddhism can be practiced as a religion but says that’s not what the Buddha taught. Buddhism is a ‘science of the mind.’ Dzogchen Ponlop gives a modern image of the historical Buddha as ‘spiritual but not religious.’ Siddhartha Gautama, who became the Buddha, embarked on a ‘spiritual quest,’ eventually ‘abandoned religious practices,’ and found his own answers in an experience of enlightenment that goes beyond all belief systems….Dzogchen Ponlop [also] says: ‘You’re not required to have more faith in the Buddha than you do in yourself. His power lies in his teachings.’” This is also true for believing that H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III is a Buddha. Faith in this Buddha also lies in His teachings which is why it is so important for those teachings to be made available to Westerners.

The weak claim is that Buddhism should not be placed on either side of the distinction we make between science and religion: Buddhism and science do not conflict because they share some of the same characteristics, while differing in other respects [p. 41]: “[B. Alan Wallace] makes the important point that we shouldn’t take our terms for granted. ‘Religion,’ as we understand it today, is a modern concept. Ancient peoples didn’t carve up the world into ‘religious’ versus ‘nonreligious’ spheres. Of course, it doesn’t follow that they didn’t have something that we may have reason to call ‘religion.’ Rather, the point is that our familiar division between religion and other areas of human activity – art, philosophy, politics, and science – reflects a recent way of thinking that we should be careful not to project onto other times and places.”

Thompson denies the strong claim, that Buddhism is a “science of mind”, and sees that notion as merely a move to legitimize Buddhism in modern society. He says [p. 144]: “Religion and science may be able to coexist, depending on the attitude they take to each other, but science can’t legitimize religion, and they can’t be merged into one.” He views science as culturally different from the culture of Buddhism and resists speculating about whether some future science could extend to parts of Buddhism that are currently not considered scientific.

Thompson also points out an example of outright conflict between Buddhist ethics and science [p. 179]: “Varela gives another, different example of the interaction between Buddhism and science. This one, he says, is ‘actually quite painful.’ It’s ‘the fact that by doing biology one engages in killing animals.’ This is central to science, not peripheral. And it’s personal: it’s an act that he carries out himself as an individual person. When he stands in front of an animal, about to begin an experiment that will end with its death he often asks himself, ‘Is it really worth it? Why stick to this funny scientific approach, why not completely drop the whole thing and follow a more compassionate attitude of respect to those animals?’ He has no answer.”

Prescription

Science can do extraordinary things, but has no ethical basis. Buddhism could provide science with a holistic ethical basis, which is sorely needed. To do so would, however, condemn some scientific practices (i.e. conduct) as unethical. What can we do to facilitate applying Buddhist ethics to science? We may not be able to dictate good conduct, but we can reveal the profound Buddhist principles that relate to ethical conduct, including how they apply to science. The fact that much of modern Buddhism has not emphasized morality and ethics is also part of the problem. H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III has given discourses on this matter that take the problem back to when Buddhism first came to China.

H. H. Dorje Chang Buddha III’s teachings can help people to live better, more compassionate and useful lives. They have the effect of lessening defilements, such as greed and anger, and of promoting societies in which people care about each other, the work they do, and the universe they live in.

Such societies may benefit from science, as well. But science alone is not sufficient. People also need to recognize their faults and cultivate themselves. Science cannot do that for them. The application of Buddhist ethics to science must come from within the scientific community itself. Buddhist ethics would need to become part of scientific culture.

Modernizing Buddhism

Thompson is skeptical of plans to modernize Buddhism. For one thing, he sees such plans as inextricably bound up with science. Modernizing Buddhism would probably mean making it more like science, which does not bode well for the major aspects of Buddhism that are not scientific, including enlightenment itself. Enlightenment is nonconceptual and therefore not within the purview of science. Thompson might agree that Buddhism is scientific (empirical) in some respects, but the other non-scientific parts are a problem for Buddhist modernists [p. 144]: “Either you embrace faith in awakening and nirvana, which, according to the tradition, transcend conceptual thought — and hence can’t be legitimized (or delegitimized) by science — or you choose to believe only in what can be made scientifically comprehensible, in which case you have to give up the idea of enlightenment as a nonconceptual and intuitive realization of the ‘fullness of being’ or the ‘suchness of reality’, for these aren’t scientific concepts.”

In addition to the supposition that modernized Buddhism would be more scientific, modernized Buddhism is often thought of as universal, or “cosmopolitan” [p. 172]: “But the word ‘cosmopolitan’…has a prescriptive or normative sense in ethics and social and political philosophy. There it refers to the value judgment that we should uphold the oneness of humanity and that we should participate in cultural associations and political structures that promote that oneness and that transcend our local community or nation. The crucial question that ethical cosmopolitans face is how to balance local allegiances and special responsibilities to those near and dear with the idea of humanity as one community.” A similar question must also be asked about balancing the allegiances to Buddhist sects and communities with Buddhism as a whole. Is talk of a single lineage or sect of all Buddhism merely rhetoric?

Prescription

H. H. Dorje Chang Buddha III’s teachings and emphasis on the legitimacy of all “84,000” methods provided by Shakyamuni Buddha and His non-sectarian approach help ameliorate modernizing trends in Buddhism. This also relates to the concept of True Dharma. He does provide a litmus regarding what is correct Buddhist teaching and practice, and what is not, regardless of tradition and culture. His approach to explaining the fundamental teachings and method of propagating the Buddha-dharma is intended to make Buddhism better suit today’s practitioners. He has stated that the Buddha-dharma is not superstition and is scientific. It is the absolute truth jointly applicable to each of us and the universe. Everything is an integral whole.

He has also said that we must have a respectful attitude and not speak in terms of right and wrong. We learn and understand things on our own. We should praise the superior qualities of each sect. He has often told us that He is non-sectarian. As long as it is Buddha-dharma, He will promote it. He has explained that the various Buddhist sects were established by individual patriarchs. And he has asked that we think about this: “What is the sect of Shakyamuni Buddha? Not any sect; it is Buddhism.”

Mind is not brain

Thompson’s ideas about the brain are not materialistic, but are not strictly Buddhist, either. They are notable because of their compatibility with the Buddhist notion of cultivation. For Thompson, your relationship to the world is an essential part of how you think [p. 123]: “A bird needs wings to fly, but the bird’s flight isn’t inside its wings; it’s a relation between the whole animal and its environment. Flying is a kind of embodied action. Similarly, you need a brain to think or to perceive, but your thinking isn’t inside your brain; it’s a relation between you and the world. Cognition is a kind of embodied sense-making.” Buddhist cultivation also requires interacting with the world. Meditating on emptiness does not involve such interactions, so it is not cultivation.

But, Thompson describes this process in terms of “mindfulness” instead of “cultivation” [p. 129]: “Being mindful consists of certain emotional and cognitive skills and putting those skills into play in the social world.” Thompson also does not talk about reducing defilements by purifying one’s conduct or transforming habits, but simply describes the process of mindful living as being embedded in an environment that supports cognition, embodying a kind of cognitive support structure [p. 132]: “The idea that cognition is embedded means that cognition — especially adaptive, intelligent behavior — relies heavily on the physical and social environment, which serves to scaffold — to build and support — ongoing cognition.”

According to Thompson, this process of being mindful (or cultivating oneself) does not involve just the brain. It involves the body as a whole [p. 131]: “…it’s important to see why the very idea of mindfulness being in the head is misguided. The idea rests on a conceptually confused and empirically faulty understanding of the relationship between the mind and the brain. The brain enables cognition, but cognition isn’t a brain process; it’s a form of embodied sense-making….The idea that cognition is embodied means that it depends directly on the body as a functional whole, not just the brain….” [p. 132]: “Strictly speaking, behavior is a property of the entire coupled brain-body-environment system and cannot in general be properly attributed to any one subsystem in isolation from the others.”

Thompson thus relates sentient beings’ thoughts to culture [p. 134]: “…the kind of cognition required for planning and carrying out complex tasks is a product of a large-scale system that is made up of cultural practices, habits of attention, and ways of using the body in interaction with one’s material and social surroundings.” He thinks this point of view is an effective way to avoid and reduce “mindfulness mania”, the current mindfulness fad, with its distorted, narcissistic exclusive emphasis on the brain [p. 138]: “We need to move from focusing just on the brain to examining how cultural practices orchestrate the cognitive skills that belong to meditation. Unless the science of meditation makes this shift, it cannot help but remain complicit in the narcissism of mindfulness mania.”

Prescription

H. H. Dorje Chang Buddha III stresses the importance of Buddhist cultivation, which puts responsibility on individual practitioners for their own cultivation. In contrast, Thompson emphasizes social and environmental supports for individuals’ cognition and behavior. The analysis that His Holiness gives in “What Is Cultivation?” of what people should do to avoid narcissism is much more complete than the one Thompson gives here. But, unlike Thompson’s analysis, the account His Holiness gives is thoroughly Buddhist. He consequently relies upon belief in karma, which non-Buddhist readers may not accept. How else could it be? Buddhist thought is thoroughly inter-connected and His Holiness is not a Buddhist modernist who aspires to somehow remove or replace the concept of karma or other fundamentals of what Shakyamuni Buddha taught. I truly believe that if H.H. Dorje Chang Buddha III’s teachings were made available to and accepted by the general public, many of the problems that Thompson articulates so well could be solved.

CLICK for my comments on the book and other links.

Add comment